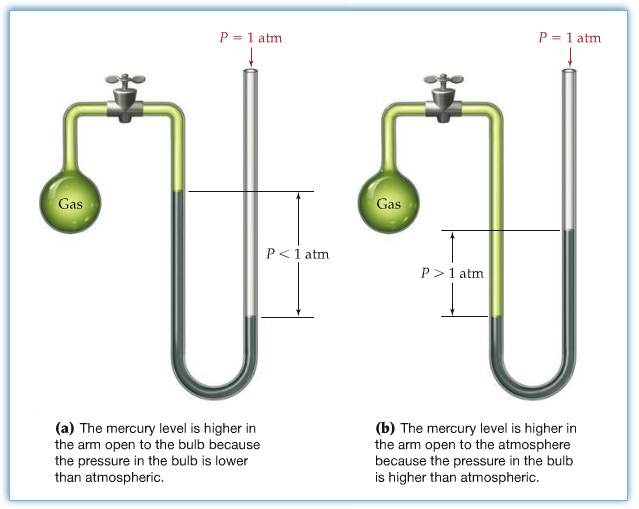

Substances That Exist as Gases

Gas Pressure

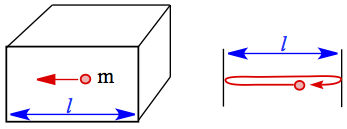

Pressure is created by collisions of molecules to the wall

Higher the pressure → more collisions b/w molecules/area/time

Pressure is

with F = force, A = area, m = mass, g = gravity, and d = density. In deriving the expression, we used F = ma and m/A = dh.

Unit of pressure = Pascal (abriviated with Pa) = 1 kgm/s2

Barometric pressure = A column with 1 m x 1 m area and a height extending to the stragosphere containing air exerts 101325 Pa.

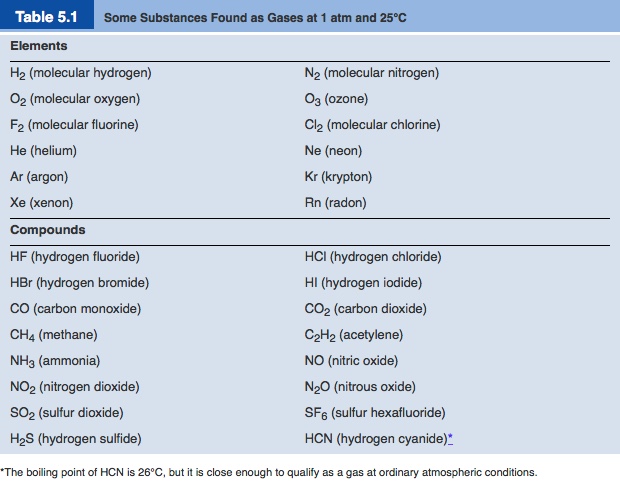

Mercury Column Barometer

Torrichelli (1643) used a column of mercury

At sea level height of columen measured = 760 mmHg

Define 760 mmHg = one standard atmosphere or 1 atm

Gravity (g = 9.800665 m/s2) pulls down mercury ⇄ air pressure pushes mercury (d = 13.595 g/cm3) up

Example: A barometer is filled with percholorethylene (dper = 1.62 g/cm3). The liquid height is found to be 6.38 m. What is the barometric pressure in mmHg?

Since PHg = Pper, and expand each P with P = dgh (make sure to label each with subscripts!)

dHghHg = dperhper

hHg = dperhper/dHg

hHg = 1.62 g/cm36.38 m/13.595 g/cm3

hHg = 0.760 m = 760 mm = 1.00 atm

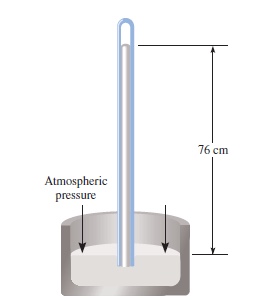

Manometer

Manometer = device to measure gas (well, just a flast with bent tube attached as shown)

If the gas inside the flask exerts the same pressure (Pgas) as atmosheric pressure (Patm), the level of liquid in the tube must be leveled. Let's call it, Δh = 0.

As seen on the graph left

If Pgas < Patm → Δh < 0

This is the case for (a)

If Pgas > Patm → Δh > 0

This is the case for (b)

Ideal Gas Law (IGL)

4 gas laws combined. 1) Boyle's Law, 2) Charles' Law, Gay-Lussac's Law and 4) Avogadro's Law

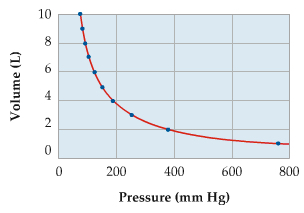

Relationship b/w P and V

Pressure is inversely proportional to Volume

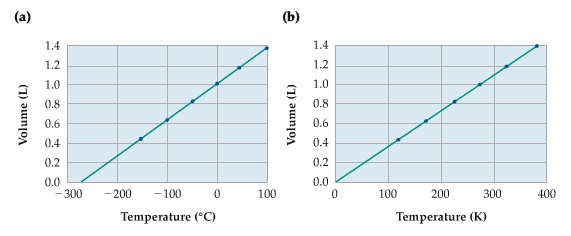

Relationship b/w Volume and Temperature

Volume is directly proportional to Temperature.

When the volume is plotted against temperature in the centigrade scale (a) in the graph, the temperature at which volume becomes 0, is the absolute 0 temperature. So, in (b) we rescale the temperature scale, called absolute temperature scale (the unit is called Kelvin, K).

Pressure is directly proportional to Temperature.

Volume is directly proportional to a number of moles.

| 2H2 | + | O2 | → | 2H2O |

| 2 mol | 1 mol | 2 mol | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 2 L | 1 L | 2 L |

Combining the four laws

P = cT

V = cT

V = cn

then

PV = ncT, and let us call c as R to obtain

Ideal Gas Equation

Let's use the IGL eqn to do some calculations!

Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP)

T = 0 °C = 273.15 K; P = 760 mmHg = 1 atm Solve for V and substitute the numbers in,

When the volume of one mole of gas is measured, Molar Volume @STP = 22.4 L.

Initial-Final State Problem

Since R is a constant, the ratio of PV and nT is also constant.

If we have a gas in a container (initial state, labeled with subscript i), we can modify the condition to the gas (final state, labeled with subscript f). These two states are related by R as

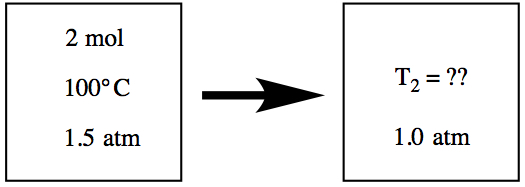

Example:  We have a vessel containing 2 mol of gas at

100°C and at 1.5 atm,as seen in the picture.

We have a vessel containing 2 mol of gas at

100°C and at 1.5 atm,as seen in the picture.

If the pressure of the vessel is reduced to 1.00 atm, what is the temperature of the gas?

Since we didn't change the vessel during the experiment, the volume should be the same, and since we didn't open the vessel, number of gas molecules are the same before and after. It means that

Molar Mass

The molar mass, μ with m and n are mass and # of moles, respecitvely, and its rearrangement is,Substituting above into IGL

Example: A glass vessel weighs 40.1305 g when clean, dry and evacuated. It weighs 138.2410 g when filled with H2O at 25.0°C (ρ = 0.997 g/mL) and weighs 40.2959 g when filled with propylene gas at 740.3 mmHg at 24.0°C. What is the molar mass of propylene?

For propylene gas, we know P and T, so in the above equation for molar mass, we need to obtain m and V.

The mass of the gas is the difference b/w the mass of gass-filled vessel and of the empty vessel, i.e. mgas = mgas+empty - mempty.

The volume of the gas, which equals the volume of the vessel, is obtained by knowing the mass of water in the vessel. The mass of water is converted to volume by its density given.

mH2O = mH2O+empty - mempty

VH2O = mH2O[ 1 mL / 0.997 g ]

Then, substitue these into the expression for molar mass, as

μ = 42.08 g/mol

Gas Density

Rearranging the molar mass equation above, recognizing that m/V is density, ρ, therefore,

@ 0°C ρ = 1.2922 kg/m3

@15°C ρ = 1.2250 kg/m3

@20°C ρ = 1.2041 kg/m3

@30°C ρ = 1.1164 kg/m3

Solve for T in the density equation.

Then, T = (μ P)/(R ρ) = 382.26 K or 109°C

Add picture here!

The density of gas can be calculated from the equation above, i.e. Using the density, we can calculate how many water molecules are in the volume (1 cm3). So, this value of 2 X 1019 water molecules are in three dimension. You can take the cube root of it to obtain the number of water molecules available in 1-dimension. So, we use this value in 1 cm as conversion factor and ask how many nm are there in 1 H2O molecule. So, between molecules there are about 3.7 nm. According to the Internet source, the diameter of one water molecule is about 0.275 nm. So, at least about 10 times the size of the molecule is the neighboring water.

Gase Stoichiometry

Relating the amount of gas of reactant or product to other species in the reaction by stoichiometry. Notabean: PV = nRT only applies to gas species in the reaction!!

a) How many L of H2 would be formed at 742 mmHg an 15°C if 25.5 g of zinc was allowed to react?

b) How many g of Zn would you start with if you wanted to prepare 5.00 L of H2 at 350 mmHg and 30.0°C?

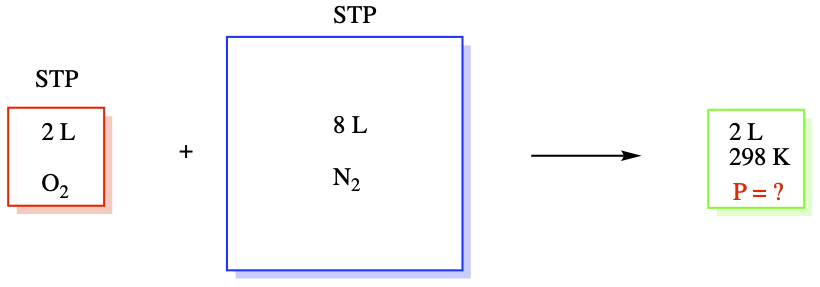

Partial Pressures: Mixture of Gases

As long as gases are inert (don't react each other), the total # mol, N, is the sum of the # of moles of each molecular species (n1, n2, ...)

The situation is summarized by:

Similarly, nN2 = 0.356909 mol. So, N = n(O2) + n(N2) = 0.446136 mol.

Partial Pressure

The sum of the component gas pressures of a gas mixture, is the total pressure of the mixture.

Ptotal = P1 + P2 + P3 + ...

with Pi is the partial pressure of ith gas.

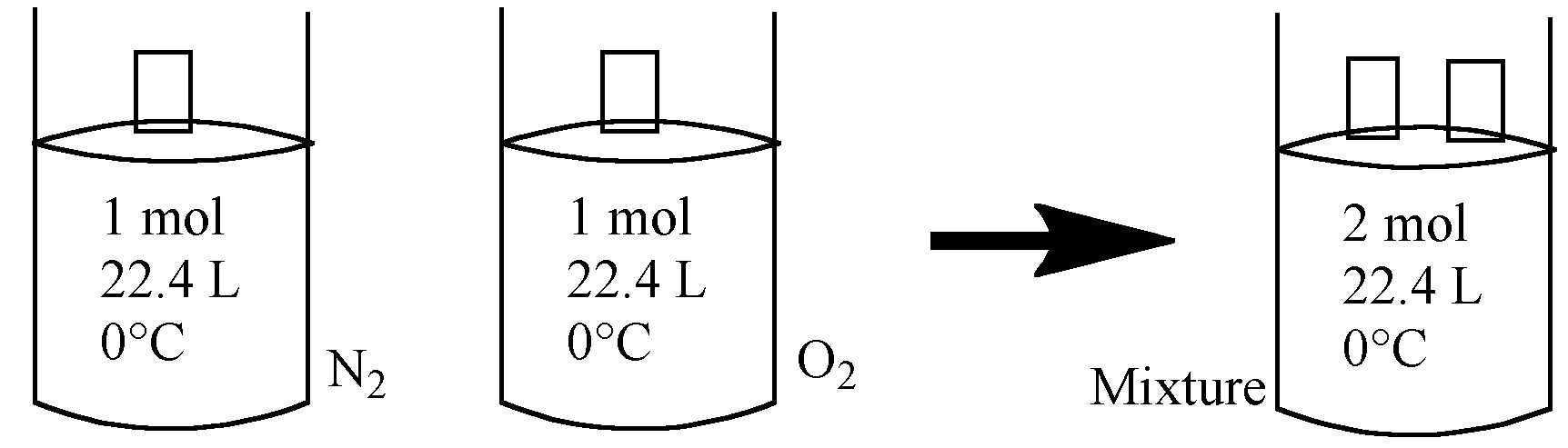

Let's suppose that we have N2 @STP with the volume 22.4 L in one container. It means that we have 1 mol of N2. In antoher container with its volume 22.4 L, we place O2 @STP. So, it also contains 1 mol. Combine these gases, now we have 2 mol of gas, keeping volume V (22.4 L) and temperature T (0°c or 273.15 K) constant. The pressure should then be 2 atm.

So, combined gas has Ptotal = PN2 + PO2

The total pressure is,

Furthermore, we have the relationship

So, if we take the ratio between PN2 to Ptotal you get,

The ratio of mol of ith component and the total # of moles is called mole fraction, χi. Then, we can calculate the partial pressure of N2 by knowing χN2 and Ptotal as

Similar conclusion can be made for VN2 / Vtotal = χN2 if we consider constant P and constant T.

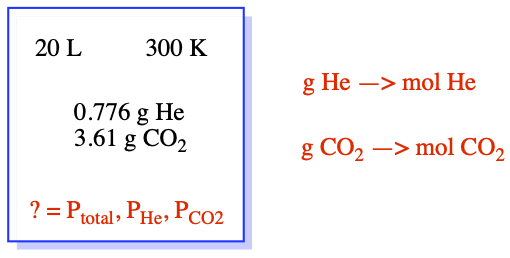

We have, V and T. The total number of moles, n, can be calculated by converting the mass to mole. So, the total number of moles is 0.19385 + 0.085907 mol = 0.27975 mol.

The partial pressure is obtained from mole fractions.

From these, we can get partial pressures

Let's assume at the course of measurement, P, V, and T are constant. Consider Earth as a big container, and its volume doesn't change. Also, if one considers that average pressure at sea level to be fairly constant, we can justify that P, V, and T are constant. Then, we can say that,

It means that χs are

| species | χ | Pi |

|---|---|---|

| χN2 | 0.7808 | 0.768 atm |

| χO2 | 0.2095 | 0.206 atm |

| χAr | 0.0093 | 0.00915 atm |

| χCO2 | 0.00036 | 0.000354 atm |

After reaction, the temperature was returned to 100.0°C, and the mixture of CO2, SO2 and unreacted O2 is found to have a pressure of 2.40 atm. What is the partial pressure of each gas in the product mixture?

Before the reaction was carried out, we have the values of P, V and T, therefore we can calculate the total number of moles of gases in the reactant mixture from PV = nRT. Similarly, we can calculate the total number of moles of gases in the products and excess O2. Let us call nreact and nprod for the respective number of moles.

Each of the gas molecules is stoichiometrically related. Before the reaction, the total number of moles of all gas species is,

We also know the total number of moles of gases after the reaction,

Since 1 mol of CS2 reacts with 3 mol O2, producing 1 mol of CO2 and 2 mol SO2, we can rewrite the nreact and nprod in terms of number of moles of CS2, such that,

Now, in the above two equations, we have two unknowns. If we solve for nO2excess in the second equation, we have,

Substitute the above into the nreact equation, we get,

which is,

Therefore, the number of moles of CS2 is now,

Now that we know the number of moles of CS2, we can relate all other species by stoichiometry in the reaction.

nCO2 = nCS2 = 0.196 mol

nSO2 = 2nCS2 = 0.392 mol

nO2excess = nprod - 3nCS2 = 0.784 mol - 3(0.196 mol) = 0.196 mol

From these, we can finally calculate the product mole fractions, χ.

χSO2 = 0.392 mol / 0.784 mol = 0.500

χO2excess = 0.196 mol / 0.784 mol = 0.250

PSO2 = 2.40 atm (0.500) = 1.200 atm

PO2excess = 2.40 atm (0.250) = 0.600 atm

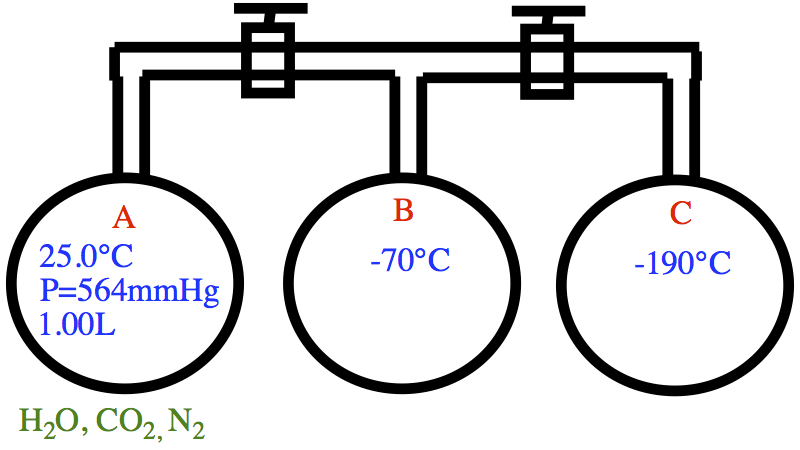

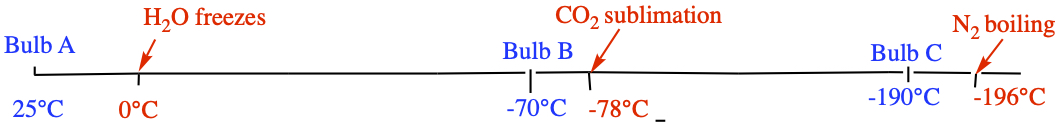

The situation is this:

b) To calculate the number of moles of H2O, we need to know the number of moles of gas in bulb A and bulb B separately since these two bulbs have different temperature.

The pressure in both bulbs is So, in bulb A, In bulb B, The total number of gas molecules are then, ntotal = 0.029068 mol. Then, the number of moles of water is 0.03033 mol - 0.029068 mol = 0.001262 mol = 1.26 x 10-3 mol.

c) Now all valves are open. P in each bulb is 33.5 mmHg = 0.04408 atm. Since bulb C is -190°C, CO2 is frozen. So then the contents of each bulb are: bulb A == only N2, bulb B == N2 and H2O, and bulb C == N2 and CO2.

d) As in part b), we can calculate the number of moles of N2 in each bulb, as The total number of moles of gas, which is N2, is 0.010906 mol.

e) The number of moles of CO2 is

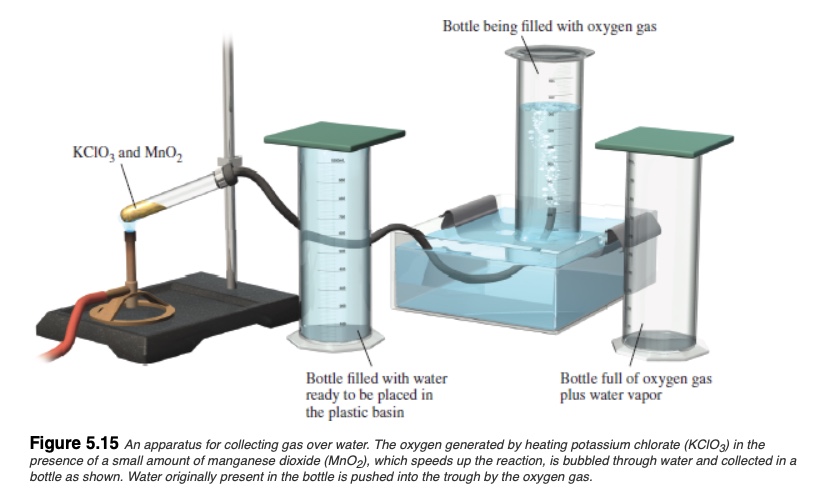

Collecting gas over water

Experimentally, a convenient set-up for collecting gaseous species are often done over the water, as shown below.

Kinetic Theory of Gases

IGL at molecular level -- meaning of kinetic energy (thermal energy)

Our model

Using this model we can derive the expression for pressure,

where N is the # of molecules, m is the mass of the molecule in amu <ν> is the average velocity of gas, and V, is the volume of the container.

If you want to see the derivation of the pressure expression, click below!

Let us first solve for

Looking at the equation above, we see that PV in the numerator

can be replaced by nRT, as we're still dealing with the ideal

gas. Then, we have,

The last equal sign is given by recognizing that Nm/n is the molar

mass of the molecule, since m is the mass of the individual

molecule, and if we have one mole (hence 6.022 X 1023 of them),

the term is the molar mass.

Meaning of Kinetic Energy

From Newton's law of motion, we know that kinetic energy, EK = 0.5 mv2, we can derive expression for kinetic energy for gas, with R = 8.314 J/molK (another way to express the gas constant, also 1 J = 1 kgm2/s

If T → 0, EK → 0

Furthermore, the average speed of the gas molecules, as obtained above, is

Therefore, the speed of molecule depends on the molar mass and temperature. Heavier the molecules, slower the speed at given temperature. The speed is higher at higher temperature.

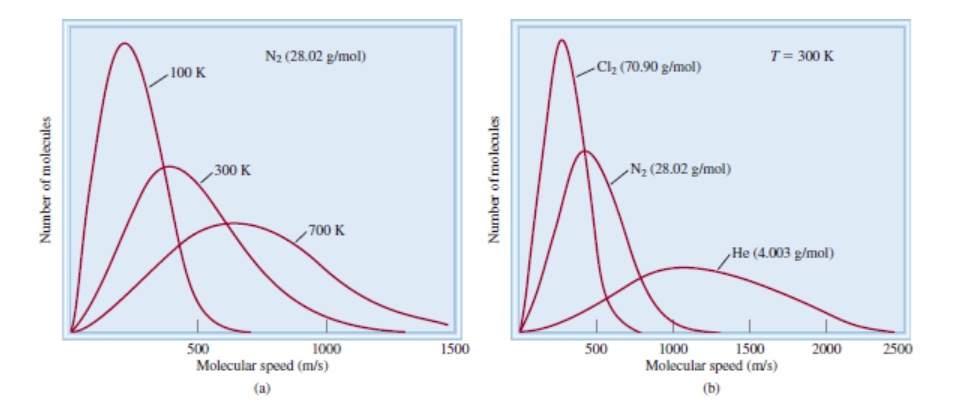

The following figure illustrates the how molecular speed is distributed among the population of gases and at different temperature.

The panel on the right shows at one temperature, distribution of different molecules, hence the molar masses, pare plotted. Lighter molecules have broader distribution while the heavier molecules have sharper distribution.

The volocity in m/s unit is more appropriate than mi/hr.

The following is nearly the same question as above.

Gas Diffusion and Effusion

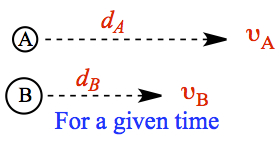

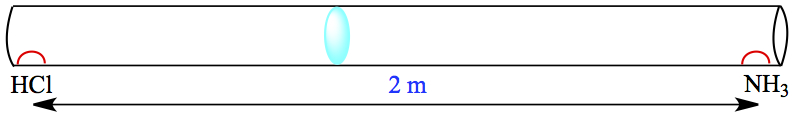

Consider two molecules, lighter A and heavier B, moving in one direction, as shown on left. For a given time interval, distances covered by the molecules differ according to the velocity equation, which depends on molar mass. Lighter molecule travels further for a give time interval, if the two gases are at the same temperature. We can obtain the relationship between the distance traveled is given by the following ratio. This is called Graham's law of diffusion

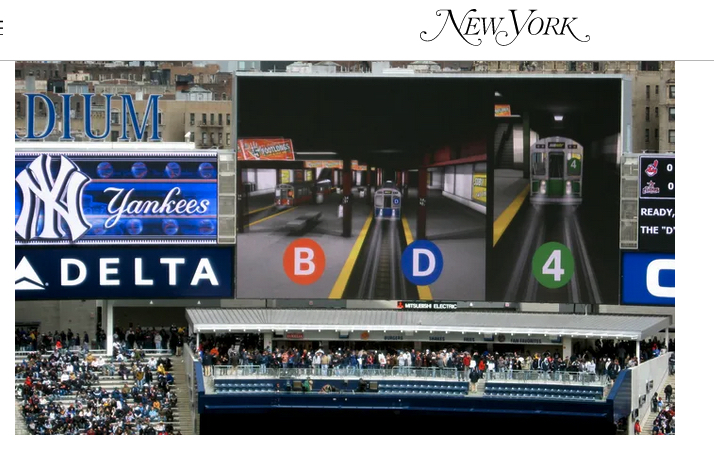

We can use this equation to have a subway (molecule) race, just as seen at the Yankee stadium, between molecules!

Seen at New York magazine.

Deviation from Ideal Behavior

Ideal gas assumptions:These assumptions fail at high pressure, as shown below!

The plot is drawn so that compressibility, (PVm/RT), is plotted against pressure, P. Vm is the molar volume; volume of 1 mol of gas.

If the gas behaves as ideal, meaning that it follows IGL, the gas would follow the blue curve. However, real gases behave quite differently at high pressure.

If one takes into account of the excluded volume and molecular interactions, one can obtain the following eqn, called van der Waals' eqn. where a and b are the constants specific to gas molecules.