AT least poker tables have some atmosphere, a jingle of highball glasses, a hint of 1990s menthol smoke in the armchairs, the sweet musk of nearby cash. The same goes for playing the horses: there are characters, scandals, competition, not to mention real payoffs.

But who, exactly, wants to stamp their frozen feet waiting in line outside a corner store for an infinitesimal shot at winning the lotto?

The answer, of course, is millions of Americans, who last week pushed the 12-state Mega Millions total to $390 million, half of which was claimed on Wednesday by Ed Nabors, a Georgia truck driver.

A 2002 nationwide survey found that lotteries are by far the most popular form of gambling, with some 66 percent of United States adults having played in the previous year, and 13 percent on a weekly basis.

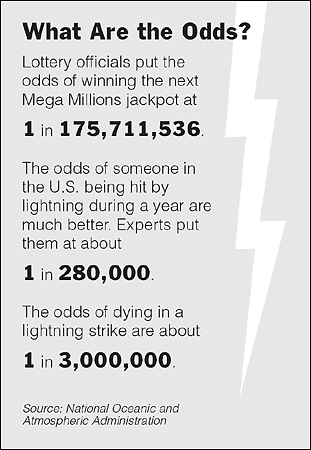

The question is why. Mega officials put the odds of winning the next big score, $12 million, at 1 in 175,711,536, and anyone with a semester of high school math can see what a fool’s bet that is. Generally, experts say, state lotteries return players about 50 cents on the dollar. And there are many people who seem to compound their folly by buying hundreds of tickets at a time.

Addiction researchers and some economists struggle to explain this behavior, describing it at best as an irrational fever, and at worst a pathological addiction to a regressive, government-run numbers game.

But researchers spend little time in corner-store lines.

“The people who denigrate lottery players are like 10-year-olds who are disgusted by the idea of sex: they are numb to its pleasures, so they say it’s not rational,” said Lloyd Cohen, a professor of law at George Mason University and author of an economic analysis, “Lotteries, Liberty and Legislatures,” who is himself a gambler and a card counter.

Dr. Cohen argues that lottery tickets are not an investment but a disposable consumer purchase, which changes the equation radically. Like a throwaway lifestyle magazine, lottery tickets engage transforming fantasies: a wine cellar, a pool, a vision of tropical blues and white sand. The difference is that the ticket can deliver.

And as long as the fantasy is possible, even a negligible probability of winning becomes paradoxically reinforcing, Dr. Cohen said. “One is willing to pay hard cash that it be so real, so objective, that it is actually calculable — by someone, even if not oneself,” he said.

The mundane simplicity of the lottery only reinforces the attraction. Casino card tables can be intimidating, an opaque world of rules and hard-to-master strategies; ditto for the track.

Because it is pure luck, the lottery is easy to grasp and allows for plenty of perfectly loopy — and very enjoyable — number superstitions. Your birthday digits never won you a dime? Try your marriage date; your favorite psalm verse; the day your bullying father-in-law died. Or, perhaps, reverse the order. In studies, psychologists have found that ticket holders are very reluctant to trade their tickets for others, precisely because they have an illusion of control from having picked magical numbers.

This sense of power infuses the waiting period with purpose. And the hope of a huge payoff, however remote, is itself a source of pleasure. In brain-imaging studies of drug users, as well as healthy adults placing bets, neuroscientists have found that the prospect of a reward activates the same circuits in the brain that the payoffs themselves do.

“It’s not just winning the money but anticipating winning the money that is exciting, and the two experiences are similar neurobiologically,” said Christine Reilly, executive director of the Institute for Research on Pathological Gambling and Related Disorders, in Medford, Mass.

People who gorge on lotto tickets, buying 100 at a time even after years of luckless playing, are no less rational than anyone else making big bets. And lottery odds are neutral and fair, after all, not biased toward any social elite. Seeing a Georgia truck driver win proves that in players’ minds.

Large rewards make most people reckless, whether they’re on the winning or losing end. A 2003 University of Vermont study found that lottery players who said they preferred to receive potential winnings in annuity payments — generally thought to be safer than receiving the money all at once, in a lump sum — often changed their minds when they actually won. And the higher the jackpot, the more likely people were to prefer a lump-sum payout, the researchers found. (Mr. Nabors chose a lump sum.)

Likewise, studies of stock traders have found that, when behind late in the day, they are more likely than usual to make risky bets, and take heavier losses, in an attempt to get out of the red.

“The point is that, psychologically, we think of a loss as a loss, big or small,” said Dr. Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “And once you’re into it, you think: Well, why not take a bigger loss, if there’s some chance I can turn it into a gain?” Similarly, people who feel that the opportunities to succeed in life are narrowing, are more likely to play the lottery, or play more often.

Households with regular players spend an average of about 2 percent of their income on the game, studies find. The proportion is higher among very low-income households.

But in most cases all the odds and numbers seem to pale next to the simple pleasure of possible transformation.

“I don’t know what I’ll do if I win,” one man standing in line told a reporter last week. “It’s too much money to think about.”

Exactly.