September 2, 2002

Laid-Off Workers Swelling the Cost of Disability Pay

illions of low-skilled workers have turned to federal disability pay as a refuge from layoffs in recent years, doubling the benefit's cost and, with little notice, making it by far the government's biggest income-support program.

illions of low-skilled workers have turned to federal disability pay as a refuge from layoffs in recent years, doubling the benefit's cost and, with little notice, making it by far the government's biggest income-support program.

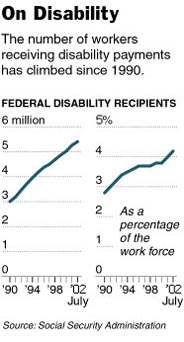

Most of those qualifying for the benefits, part of the Social Security system, never got past high school and held jobs like factory worker, waitress, store clerk, laborer or health care aide. Their numbers have grown to 5.42 million today from 3 million in 1990, swelling the program's costs to $60 billion last year. That far surpasses unemployment insurance or food stamps or any other similar program.

"Show me a high school dropout, particularly a male, who is over the age of 40 and is not working and there is a 40 to 45 percent chance that he is on Social Security disability insurance," said David H. Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

It is not that disabling injuries are occurring more frequently or that more people are cheating a system that requires considerable evidence to prove disability. Research by a number of economists indicates that the growing numbers signal instead a reliance on disability benefits by low-end workers who had ignored their ailments as long as their limited skills brought them steady employment. Some who would have gone on welfare now apply for disability pay instead.

"When you are a person who has lost a job, and you can't find another and you are home sitting on the couch," said Morley White, an administrative law judge in Cleveland who rules on disability claims, "you become preoccupied with ailments that do qualify in many cases as legal disability but while you were working did not come into your mind."

Neither Congress nor the White House has challenged the skyrocketing cost of disability insurance, which will go up an additional $9 billion this year, reaching $69 billion, the Social Security Administration estimates. By comparison, the agency expects to pay out $382 billion in traditional old-age pensions in 2002, financing both pensions and disability payments through the same payroll tax. The debate on the financial health of Social Security has focused on the much larger pension system.

"There was always a bigger issue in the news to distract us and disability just crept up on us," said Kevin M. Murphy, a University of Chicago economist. "It is the tortoise in the tortoise and hare story."

The surge in the disability rolls started with the early 1990's recession, and the numbers climbed steadily as layoffs became common, even in the boom years of the late 90's. Hard times over the last 18 months produced another surge in the disability rolls, which grew by nearly 400,000 people in that period, unevenly across the country. State officials process the disability claims, acting as agents for Social Security, and some states have been more generous than others.

"In tough times, there is a tendency at the state level to cut people a little slack," said Charles A. Jeszeck, a labor economist at the General Accounting Office.

The rising numbers of people on disability take some of the gloss off the prosperity of the late 1990's. Unemployment fell and in the tight labor markets jobs went begging, even at the low-paying end. But the Labor Department counts as unemployed only those people actively seeking new jobs. When people stop looking and drop out, including people who go on the disability rolls, they no longer count as unemployed.

Those dropouts surged in number in the late 1990's. There were so many that if they had been counted as unemployed, the unemployment rate would have been higher, perhaps by as much as half a percentage point, according to new research by Dr. Autor and Mark Duggan, a University of Chicago economist.

Not all of the dropouts applied for disability pay, of course, but many of them did, Dr. Murphy found in a study he did with Robert H. Topel, also a Chicago economist, and Chinhui Juhn of the University of Houston. "More than 40 percent of the growth in nonparticipation is associated with an increase in men claiming to be ill or disabled," the three wrote in a recently published paper.

The 5.42 million people on disability pay, receiving $819 a month on average, is equal to 4 percent of those who hold jobs today. That increased from 2.5 percent in 1990, after barely rising at all in the 1980's, although Congress broadened the definition of disability and made proving it easier in 1984. It became particularly easier in the cases of back trouble and mental health problems, which can now include depression, manic behavior and other "mood disorders." Back trouble and mental stress are the two most cited ailments in disability awards.

"You have to be basically unable to function in a working environment," Dr. Autor said about the broader guidelines. "Before 1984, you had to have a specific qualifying ailment, like schizophrenia or a broken back."

Seventy-five percent of those on disability have a high school diploma or less education, the Social Security Administration reports. Their limited skills mean they are often still without a job five months after being laid off — the minimum time required to file for disability pay. Magnifying the problem, the low skilled find themselves mostly holding jobs that require physical exertion, Judge White said, and any ailment becomes an obstacle to landing the next job. So they turn to disability.

"I think that people who are better educated with transferable skills and other opportunities do not have to come before me to claim disability," the judge added.

Gregory Jordan, a 51-year-old former dock worker in Long Beach, Calif., is certainly familiar with the disability appeals system. He has just started to receive a $560 monthly disability check, five years after suffering the injury that disabled him. On a windy day on the docks in April 1997, a rear door of a tractor-trailer swung into Mr. Jordan's back.

"I completely blew a disk out," Mr. Jordan said, explaining that he had gone back to work after the accident and had continued on the job until Christmas, when the pain finally forced him into a hospital and he learned the extent of his injury. Workmen's compensation payments soon started, and they will continue alongside the disability checks. Like old-age pensions, disability pay is based on former earnings and not on need, as welfare is.

In telling his story to a reporter, Mr. Jordan recounted the case he made to disability officials to justify his claim: six back operations, constant use of pain killers, nerve damage affecting his arms, hands and legs. With only a high school education, his opportunities away from the docks in work that did not require physical exertion were limited. Still, disability evaluators, following Social Security guidelines, at first determined that jobs were available commensurate with his skills.

"They told me I could work at telemarketing or sitting at a desk all day answering telephones," Mr. Jordan said.

Like so many others, Mr. Jordan took his case to an administrative law judge. Although Social Security disability is a federal program, most of the states provide the judges who rule on appeals, often reversing an earlier denial. About 40 percent of all disability awards come on appeal, actuarial studies have found.

"No employer is going to hire me and take on the liability that I represent," Mr. Jordan said. "I can't stand very long, I can't sit very long. If I go anywhere I have to use a wheelchair."

Sitting or standing: those are crucial in judging whether a claimant, particularly one with little education, can "engage in a substantial gainful activity." If the person can demonstrate that because of an ailment or the pain it produces, he or she can no longer sit for six hours in an eight-hour day or stand for at least two, then that person is deemed disabled.

"Pain is the most argued thing in disability cases," Judge White said, adding that "98 percent of the people who come before me truly believe they are disabled."

No one disputes that the disability rolls are swelling. But the reasons offered vary. Social Security officials attribute the rise to the large number of aging baby boomers. In addition, many women have gone to work, thus becoming eligible for benefits. The rules require a disability applicant to have held a paid job for a total of 5 of the previous 10 years and to have earned wages for 25 percent of the time since age 22. The earnings in these years then become the basis for calculating disability.

Those explanations are challenged by some economists and policy makers. Despite the baby boomers, the average age of people on disability has fallen, they note. They argue that younger people increasingly qualify on the ground of mental illness. With the average age falling, the disabled are remaining on the rolls longer, and that has swelled the numbers. Congress helped in this process by making it harder for Social Security officials to declare people cured and no longer eligible for disability.

"They now have to present compelling evidence of an improvement in health," Dr. Autor at M.I.T. said.

There are other explanations. Lawyers, for example, increasingly help applicants with their claims, earning fees if the claims are awarded. The disability payments themselves have been rising at a faster rate than the pay of most low-end workers, gradually making paid employment less attractive for the unskilled, said Lawrence Katz, a Harvard University labor economist.

There's another lure, particularly for the unskilled who often work without company-paid health insurance. Two years after the disability checks begin to arrive, Medicare coverage kicks in free.

Cost-cutting proposals are beginning to appear. Douglas Besharov, a scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, for example, would make modern drugs available at little or no cost to the mentality ill on disability so they could work again, thus cutting the rolls. But he sees little chance of change now.

"This is the wrong election cycle to talk about cutting back anything," he said. "I think the lesson of the last year is that the Democrats want to paint the Republicans as mean and the Republicans are willing to spend tens of billions of dollars to avoid being called mean."

One approach to trimming the rolls that might not be dismissed as mean spirited is a proposal by Kenneth S. Apfel, a commissioner of Social Security in the Clinton years, to combine disability pay with retraining and part-time work.

"It would help the large number of people in their late 50's who have become obsolete workers and have some medical condition," said Mr. Apfel. "It would give them a bridge to retirement at age 65 when they are shifted anyway from disability pay to regular pensions."